How society has changed

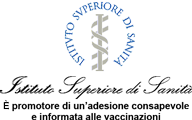

The cultural level of the population in recent years has undergone a profound change. In 1951 in Italy, 31% of the population were illiterate1 and most of those who had attended school (60%) were educated up to primary school level (figure 1).

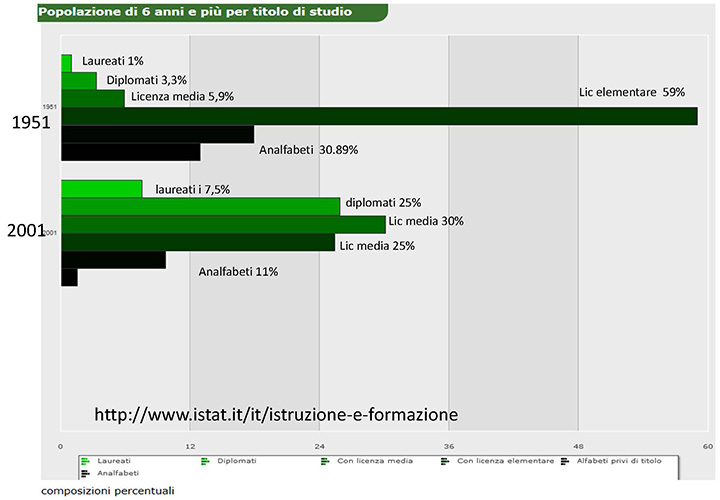

In 2001, the situation was already radically different: over 55% of the population had a level of education at least up to middle school, and 7.5% had a degree. This evolution determines a different way of dealing with health issues: in the past, the doctor was a paternalistic figure who did not need to convince but had only to dispense, today he must be a trusted advisor who enables the patient to select the most suitable course in an informed and aware way. Nowadays, most patients obtain information independently, sometimes consulting their doctor only at a later date. The advent of the internet has brought about a new means for looking up information: almost 30% of the population use a computer at least once a day and connect to the Internet (figure 2).

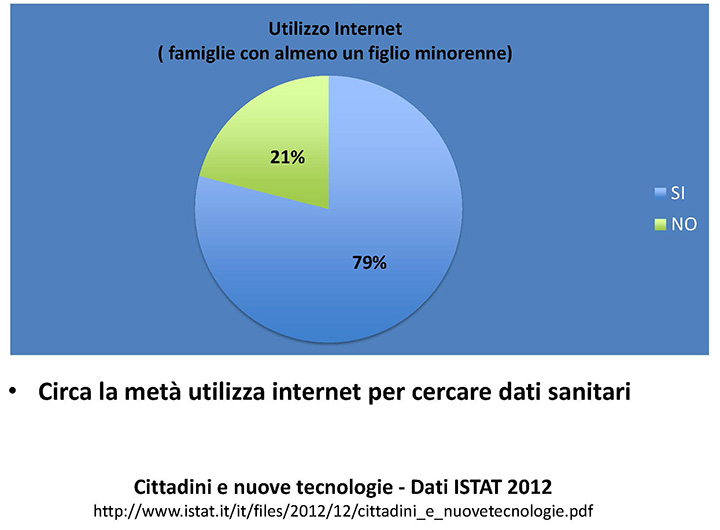

In the case of households with at least one minor - the case of most interest to us - the figures rise to 80%, of which half claim to use the Internet to look up data regarding health2 (figure 3).

Why get vaccinated?

In post-World War II Italy, the difficult socio-cultural conditions of most of the population necessitated the introduction of mandatory vaccinations; nowadays this obligation is becoming less and less necessary. In Veneto, for example, it was suspended and vaccination coverage was unaffected. For some time, there was no talk of compulsory and optional vaccinations but only of recommended vaccinations. Vaccination should be considered a health opportunity to be sought after and not an obligation to be avoided.

The determinant factors for adherence to vaccination programmes originate from doctors, local paediatricians, and from public health programmes. In the majority of cases it is the mother who takes on the responsibility of seeking the most suitable preventive practices for the child.

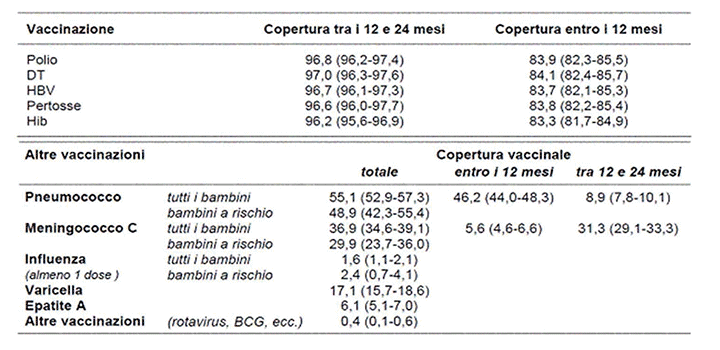

In Italy, the most recent study to analyse this topic was the ICONA 2008 survey3. In total, the families of 3,806 children were interviewed. The study was carried out through interviews: in 85% of the cases the mothers responded, while the fathers responded in only 12%. It can be seen that for children between 12 and 24 months, for compulsory vaccinations, offered free-of-charge with the hexavalent vaccine, coverage is satisfactory and ranges from 96% to 97%. The situation is different for other vaccinations such as the Measles-Mumps-Rubella vaccination, for which coverage is around 90%, therefore still below the level of (95%) foreseen by the national plan for the eradication of measles and congenital rubella (Piano nazionale di eradicazione del morbillo e della rosolia congenital). (figure 4).

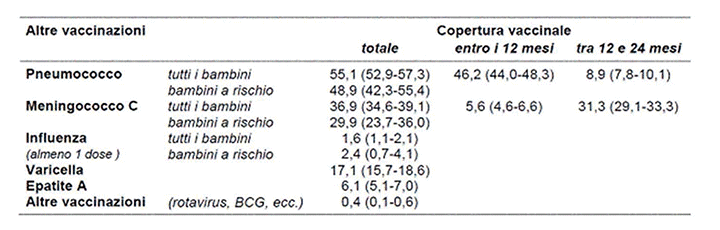

For other vaccinations (Pneumococcus, Meningococcus C, Varicella, Rotavirus, Influenza) coverage is much lower; it is therefore essential to try to understand the reasons for this (figure 5).

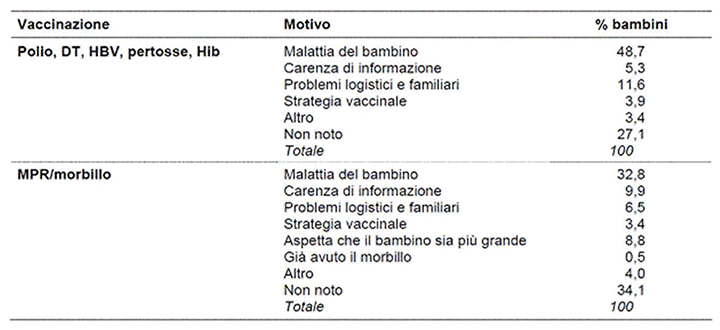

For the hexavalent vaccine, the main reason stems from the child’s state of health (48.7%), while for Measles-Mumps-Rubella this motivation is reduced to 32.8%, whereas the lack of information about the vaccine increases to 9.9%. This makes it clear that mothers have few problems with vaccinations deemed mandatory, which they tend to undertake unless the child is sick, while for the others more information is needed. Finally, the information factor becomes decisive for vaccinations that are not well known in Italy and that are carried out only in some regions (Pneumococcus, Meningococcus C, Varicella, Rotavirus, Influenza) (figure 6).

For these, the advice of the paediatrician is therefore fundamental. In particular this is noticed for influenza: the paediatrician's advice leads to vaccination in 66% of cases.

In light of these data, it is clear that in Italy vaccinations are taken if considered mandatory while vaccinations that are not sufficiently known are more problematic. When adherence to mandatory vaccination begins to fall, it becomes important that they are undertaken following careful consideration and it is essential that parents (mothers) can avail of proper health education.

But what are the mental dynamics that lead mothers to decide about their children’s vaccinations? There are several studies4 that have identified significant positive and negative factors in relation to attitude towards vaccination. Positive factors include: preventing disease; helping the community by participating in herd immunity (the so-called "social contract"); respecting the cultural norm (bandwagoning, i.e. doing what most others do). Some of the negative factors include: the fear of side effects; the so-called "reversed social contract" i.e. if others are vaccinated, the risk decreases (free-riding); the belief that there is less guilt involved in doing nothing than in doing something; considering the disease to be very rare; the theory that it is better to develop natural immunity rather than to vaccinate.

The hypotheses outlined above stem from quantitative studies5 that are not always able to investigate the full range of maternal attitudes. Furthermore, qualitative research provides a better method for describing phenomena such as comprehension and behaviour. It is based on inductive reasoning, in which hypotheses are derived from observations. For this reason, I report the results of a work by Benin6 (published in Pediatrics in 2006) which describes the entire range of maternal types regarding the vaccination of their children. The work was carried out in two stages by interviews with mothers who had just given birth and were then contacted by telephone for the second interview after several months. The average age of mothers was 32, with a range of 19- to 43-year-olds.

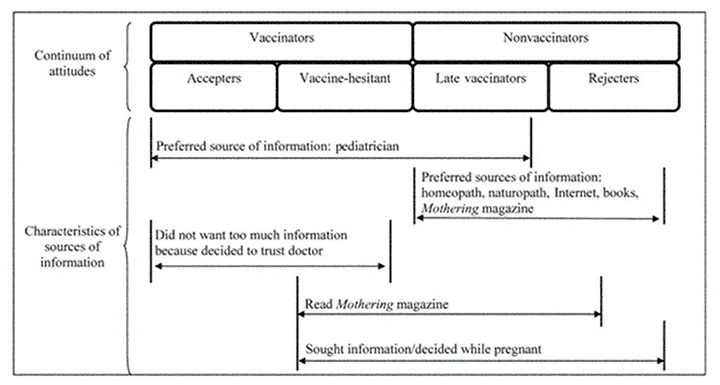

The women, based on the answers given, were divided into two main groups (figure 7): the first group is made up of women in favour of vaccination (vaccinators) and the second of those who refuse vaccination (non-vaccinators). Each group can then be further divided into two subgroups: mothers who immediately accept vaccinations (accepters) and those who accept vaccination, but with considerable fear (vaccine-hesitant). Among the non-vaccinators, there is a first sub-group of mothers who choose to delay vaccinations or to undertake only some (late vaccinators) and a group that totally rejects vaccination (rejecters). The mothers who hesitate or delay vaccination are similar to each other in their desire for knowledge; they are the ones on which it is possible to intervene and the majority have expressed the wish to have information about vaccinations from their paediatrician. Many of the women interviewed had little knowledge about vaccinations and made mistakes when discussing vaccines.

Figure 7 also shows that the sources of information are varied and determinant, in fact the mothers ultimately in favour of vaccinations (those who accept vaccination; those who hesitate and delay vaccination), receive the information from their paediatrician. On the other hand, the mothers who do not vaccinate prefer information sources including naturopathic doctors, homeopaths, books or the Internet, as well as Mothering Magazine, which includes articles both for and against vaccination and has a wide readership that includes a large number of non-vaccinators. Among the mothers who delay vaccination, there is a request for a long conversation with the paediatrician; conversely, many of the mothers who vaccinate immediately prefer to trust the paediatrician and not to choose independently.

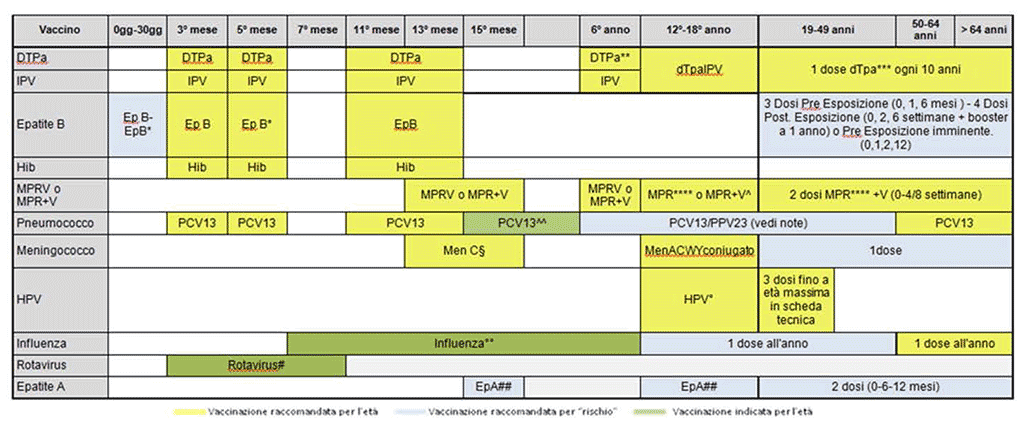

In recent years, the resistance of some parents to vaccination has continued to rise, even though the dangers deriving from vaccine-preventable diseases are clear, and despite medical reassurance regarding the safety and efficacy of vaccines. This resistance is partly due to the proliferation of articles, books and websites that question the safety and value of childhood vaccinations. Websites and blogs on the topic of vaccination are multiplying and many mothers exchange information through social networks. It is not easy for a non-expert to find their way around so much information and to distinguish what is the truthful from that designed to muddy the waters or to propel the interests of alternative medicines. Thus, the way in which doctors must respond when questioned by mothers is fundamental. Although there is generally a good relationship between parents and paediatricians - considered reliable and trustworthy and on the side of children – at times the debate about vaccination has become violent and has led to the interruption of the relationship of trust. In the USA, a percentage (ranging from 24 to 39%) of paediatricians have said they are willing to stop assisting children in families who refuse to undertake the vaccinations they recommend. We do not know who will then assist these children, but from this we can comprehend how important it is that information is properly given, without being rushed, and how useful it is to calmly address all of the families’ doubts in a homogeneous and widespread manner. To this end, it would be desirable to have audiovisual teaching aids8, derived from a consensus among doctors, which could be used for educational purposes. The FIMP (Italian Federation of Paediatric Doctors) on a national level and starting with an observation of the vaccination federalism which exists in the various Italian regions, has created a network of doctors which then published a vaccination schedule. This has recently been shared with other paediatric scientific associations such as the SIP (Italian Paediatric Society), the SiTi (Italian Society of Hygiene) and the FIMG (Italian Federation of General Medicine). This has proved particularly useful for giving precise and homogeneous indications on vaccination strategies that can be adopted in Italy (figure 8).

The Internet and vaccinations

According to the latest Istat data, 80% of parents of children of vaccination age use the internet, including to look up information about health9. The web changes the way in which information is used, in particular as regards health care content. Unfortunately, incorrect information and negative messages related to vaccinations abound at present10 and often patients who refuse vaccinations have visited anti-vaccination websites.

The Internet is continuously and rapidly changing and, in little time, evolved from Web 1.0 to Web 2.0 and we are currently entering the era of Web 3.0.

Web 1.0 now represents the past: it was static and the production of knowledge remained similar to the traditional one. On Web 1.0, a small group of people (often specialists) who held knowledge and the means to disseminate it put content on the Internet, in the same manner as in books or magazines. There was therefore a stark difference between author and reader.

Web 2.0 also known as the Participatory or Social Web, is the present one: it gives users the opportunity to interact with the pages and therefore also to produce content. There is no longer any difference between author and reader as even the reader can be an author. We have switched to dynamic and multidirectional communication, and the user can produce new content, comment and contradict existing content, and share content with other users.

Today we are moving towards the Web 3.0, the Semantic Web. There is meaningful information regarding the content and thanks to a series of metadata (tags, classification systems, taxonomic languages) computers are able to understand the meaning of the content present on the web and therefore to process it directly and use it for various purposes (to direct information, to create specific and targeted advertising). Web 3.0 has also been used to describe a path that leads to a sort of artificial intelligence capable of interacting with the Web in an almost human way, even if there are many sceptics who consider this impossible. Despite this, companies like IBM and Google are obtaining astonishing information with the use of innovative technology. For example, they can predict the most downloaded songs, through data mining, on university websites. Web 3.0 is already part of our daily life, and can be seen for example when suggestions for sites with content similar to those recently consulted appear automatically.

These changes have had numerous consequences: first of all the problem of the authoritativeness of the content arises. Who guarantees their validity? The amount of content is immense (as it can be produced so many people) and it is difficult to distinguish between correct and incorrect information. It brings us to a situation of collective intelligence: users who become authors and contribute to building knowledge. However, regarding scientific knowledge, this is often problematic. The doctor, who should be the expert, the one who advises, the one who gives the correct content, loses authority and is questioned and often overrided by the internet. At times, the one who publishes the content holds more authority (‘I read it on the internet’).

We have seen that in Italy about 80% of parents surf the net and of these 70% use the information obtained to make decisions concerning their health11. In 200612, 16% of internet users used the Internet for news about vaccinations: an online search is simpler and faster than research done traditionally through reading magazines and books or consulting a doctor. More than half of internet users believe that the information obtained is reliable13. However, the chances of finding untruthful and misleading information are very high and has meant that as far back as 1996 the internet was compared to a modern Pandora's box14.

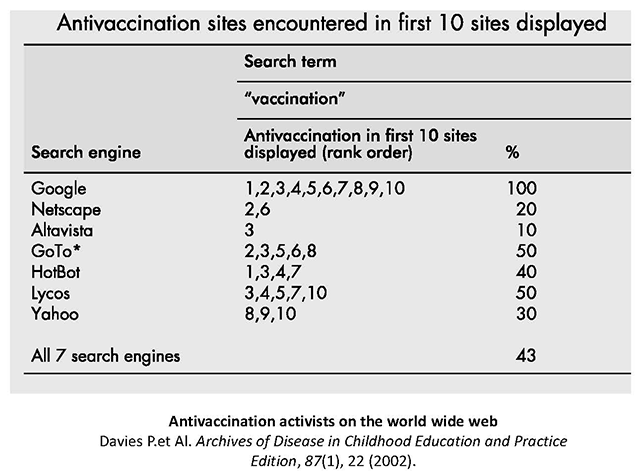

Anti-vaccination content is much more likely to be found on the internet than in other sources of information15. In a 2002 paper16, it was found that depending on the search engine used, there were different percentages of possibilities for finding anti-vaccination websites first. For example, (figure 9) using Google and looking up ‘vaccination’ the first 10 sites found were all by anti-vaccinators.

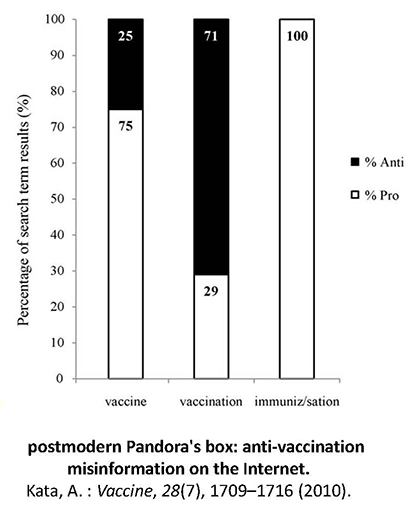

A paper by Kata10, published in Vaccine, carried out a research into several anti-vaccination websites, and evaluated the quantity of errors and misinformation they offered. In recent years, there has been an increase in the presence of pro-vaccination sites but the probability of finding websites for or against vaccinations also varies depending on the term used for the search: in fact in the US in 2002, when looking up the term ‘vaccine’ on Google17, there was a 24% percentage of displaying anti-vaccination sites, this increased to 71% if ‘vaccination’ was used, while with ‘immunization’ only pro-vaccination sites were found (figure 10).

If today you look up ‘vaccine’ on Google, the first 10 sites displayed are all in favour of vaccination, if you type ‘vaccination’ the same occurs, as it does when using the term ‘immunization’. This confirms that though initially the scientific community and institutions hardly considered the Web, today we are witnessing their ever increasing input in this direction.

However, there are undoubtedly parts of the web that are still dominated by anti-vaccinators, for example when searching on YouTube using the word ‘vaccine’, of the first 7 results 4 are against and only 3 in favour. This is confirmed by the work of Keelan18 in Jama, which underlines the importance and effectiveness of Youtube videos compared to other means of communication, in fact, videos are often more appealing and more easily followed.

Vaccination and social networks

The debate about vaccination is widely present also on social networks and blogs, where initiatives by individuals (mothers) who exchange information on vaccinations prevail. They compare their experiences, put forward their doubts, ask questions to the experts. The aim of these virtual spaces is to create a network of contacts and to gather news concerning motherhood and children.

There are also forums, which allow you to discuss topics of common interest, to suggest and organise initiatives, to create a support system for mothers, to put questions to specialists, to suggest books on the theme, but also to share doubts and concerns regarding various topics including vaccination. Examples include: Forum al Femminile (www.alfemminile.com), Pianeta Mamma (www.pianetamamma.it), Mamme di Macerata (www.mammemacerata.it), Bambini.it (www.bambini.it) Mamma e Papà.it (www.mammaepapa.it).

What emerges from this is the desire to have more opinions to try to shed light on a topic that still continues to divide a large part of public opinion. If most paediatricians recommend vaccinations, the spread of the thinking that deems them unnecessary and harmful causes a certain mistrust, and encourages people to seek different opinions.

Consulting these sites gives an overview of the different approach that mothers have towards vaccinations. The most frequent attitude is to seek and obtain information in order to have a deeper knowledge of the subject and reassurance about fears regarding side effects. The most frequently asked questions are: ‘What should we vaccinate against?’, ‘When to vaccinate?’, ‘What are the side effects of vaccines’?

This is mainly due to the diffusion of texts - paper or digital - which advise against vaccinations; these are often based on the foundations of homeopathic and naturalistic medicine. These alternative medicines claim that real protection does not lie in vaccination but in identifying highly immunosuppressed children and in strengthening their immune system through proper nutrition, adequate hygiene and specific medical interventions, almost never of a pharmacological type. The main sites are: Condav.it (www.condav.it), Mednat.org (www.mednat.org), Comilva.it (www.comilva.org), and Vaccinareinformati.org (www.vaccinareinformati.org).

However, today Twitter and Facebook also represent a playing-field. Here, while in the past the presence of private individuals and therefore of anti-vaccinators prevailed, today it is possible to follow a large number of institutional sites which, in real time, give correct and updated information on the current information regarding vaccination.

Conclusions

Pediatricians, hygienists and all doctors and health professionals must realise that nowadays, especially on the subject of vaccination, it is necessary to provide in-depth, clear and correct information, using accessible language which is immediately understood, through the modern means of communication via the Internet. The prestigious medical journal, Vaccine, dedicated an entire issue in 201219 to this problem; in the editorial entitled ‘Dr.Jekyll or Mr Hyde’, they took stock of the situation and highlighted the ocean of conflicting information on the Internet.

It is therefore necessary for physicians to give their patients indications about how to understand which sites are reliable and thus where to find information. We could summarise this as below20:

- Is the purpose and site manager clearly identifiable?

- Is the site manager and/or administrator contactable?

- Is there a conflict of interest?

- Does the site give anecdotes about the adverse effects of vaccines instead of scientific evidence?

- Is the news evaluated by scientific experts before being published? What are their credentials?

- Are facts clearly distinguishable from opinions?

At the same time, it is necessary for public health and all scientific communities to assume an online presence across all platforms (sites, blogs, social networks, forums). Public health websites will need to be indexed so that the user can find them more easily. More attention should be paid to those who are more concerned: young people, travellers, and pregnant women. The information must be balanced, and must provide a complete offer of news both on the risks of the disease and on the benefits and risks of vaccination. All doctors should also engage online in discussion forums as experts in a planned and strategic manner.

Sources / Bibliography

- Istat.it

- Istat.it - cittadini e nuove tecnologie

- ICONA 2008:Indagine di copertura vaccinale Nazionale nei bambini e negli adolescenti. ISSN 1123-3117.Rapporti ISTISAN 09/29

- D. A. Gust, N. Darling, A. Kennedy,B. Schwartz, Parents With Doubts About Vaccines: Which Vaccines and Reasons Why. Pediatrics 2008;122;718-725

- Hershey JC, Asch DA, Thumasathit T, Meszaros J, Waters V. The roles of altruism, free-riding, and bandwagoning in vacci- nation decisions. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 1994;59: 177–187

- A. L. Benin, D. J. Wisler-Scher, E.Colson, E. D. Shapiro and E. S. Holmboe: Qualitative Analysis of Mothers' Decision-Making About Vaccines for Infants: The Importance of Trust,Pediatrics 2006;117;1532-1541 DOI:10.1542/peds.2005-1728

- Flanagan-Klygis EA, Sharp L, Frader JE. Dismissing the family who refuses vaccines: a study of pediatrician attitudes. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159 :929 –934

- Levi B.H..Addressing Parents’ Concerns About Childhood Immunizations: A Tutorial for Primary Care Providers.Pediatrics, Jul 2007; 120: 18 - 26

- Istat.it - cittadini e nuove tecnologie

- Kata, A: A postmodern Pandora's box: anti-vaccination misinformation on the Internet,: Vaccine, 28(7), 1709–1716 (2010)

- Pew Internet & American Life Project. The engaged e-patient population, 2008 (ultimo accesso 26/04/09)

- Pew Internet & American Life Project. Online health search ; 2006 (ultimo accesso 29/05/09)

- Pew Internet & American Life Project. The online health care revolution: how the Web helps Americans take better care of themselves; 2000 (ultimo accesso 29/05/09)

- Mayer M, Till J. The Internet: a modern Pandora’s box? Qual Life Res 1996;5(6):568–71

- Davies P, Chapman S, Leask J. Antivaccination activists on the world wide web. Arch Dis Child 2002;87(1):22–6

- Davies P.et Al. A Antivaccination activists on the world wide web archives of Disease in Childhood Education and Practice Edition, 87(1), 22 (2002)

- Davies P, Chapman S, Leask J. Antivaccination activists on the world wide web. Arch Dis Child 2002;87(1):22–6.

- Keelan J et Al.: YouTube as a source of information about immunization. JAMA;298:2482 (2007)

- Vaccine . Special Issue: The Role of Internet Use in Vaccination Decisions. Volume 30, Issue 25, 28 May 2012

- Pineda, D., & Myers, M. G. Finding reliable information about vaccines. Pediatrics, 127 Suppl 1, S134 (2011)