The hypothesis

Some people claim that it was the improved living conditions - and not vaccines - that caused the decrease in the incidence of infectious diseases in the last century.

Scientific elements that contradict this hypothesis

At the beginning of the 1900s, infectious diseases were the leading cause of death in the USA and Western countries, as they are still today in Third World countries.

The improvement in sanitary conditions has certainly had a significant impact on the decrease in mortality from infectious diseases. The nineteenth-century migration of people from the countryside to the city had led to overcrowding in homes served by inadequate or non-existent water and sewage networks. These conditions caused repeated epidemics of cholera, dysentery, tuberculosis, typhoid fever, flu, yellow fever and malaria.

From 1900 onwards, the incidence of many of these diseases began to decrease indirectly thanks to public health actions and lifestyle improvements: the construction of sewage networks and the use of drinking water treatment systems, better living standards with less crowded environments (making it more difficult to spread diseases), better nutrition, the discovery and introduction of antibiotics.

However, the direct effect that vaccines have had on the impact of diseases, both in the past and in the present, must be taken into account alongside these improvements.

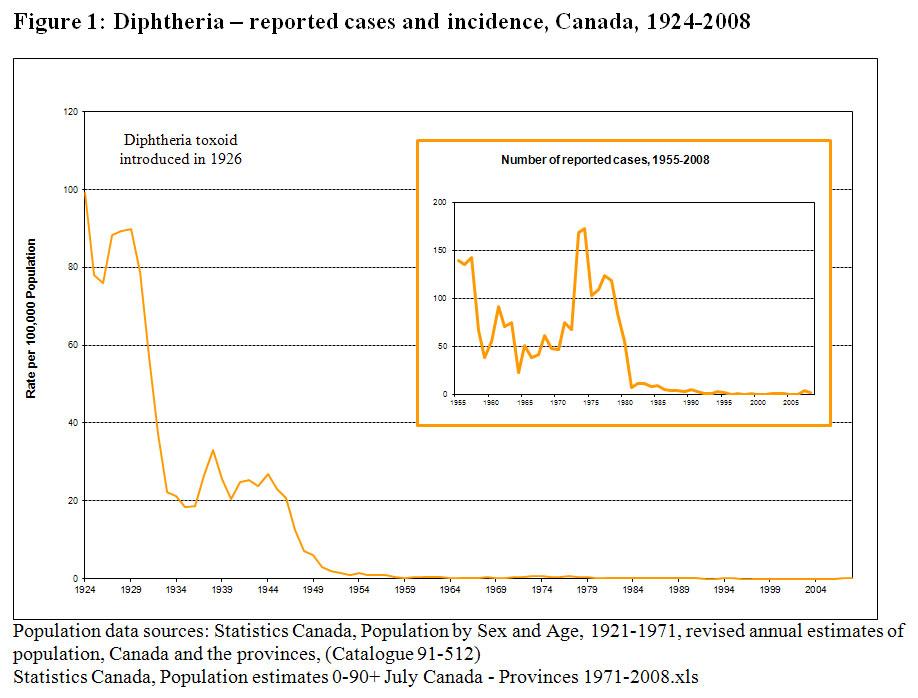

Consider the graph below: The image includes two graphs showing the reported cases and the incidence of diphtheria in Canada1. The incidence of diphtheria (largest graph) was close to 98 per 100,000 inhabitants in 1924. The introduction of the diphtheria toxoid in 1926 led to a drastic reduction in incidence, reaching and maintaining a value close to zero since 1969. The smaller graph illustrates the cases of diphtheria from 1955 until 2008. Although there have been periodic peaks and deflections over the years, the number of diphtheria cases has continued its downward trend reaching zero by 1990 and remaining close to zero ever since. Graphs for most vaccine-preventable diseases show a similar pattern.

Although there have been periodic peaks and deflections over the years, the real and permanent fall in diphtheria cases coincides with the introduction and use of the vaccine in 1926. The graphs for most vaccine-preventable diseases show a similar trend.

If the hypothesis were correct - that is if the illnesses had disappeared due to improved living conditions - we should expect a gradual decrease in the cases of the disease, and not rapid changes.

However, Italian data on polio shows the opposite. Vaccination began in 1964. Disease cases were reduced immediately. In the second half of 1964, 212 cases were declared, compared with 1,800 and 2,300 in the same period of previous years. In other words, the number of cases has fallen by almost 10 times and this cannot be ascribed to the improvement of hygienic conditions.

Furthermore, if the hypothesis is correct, a similar and overlapping decrease in all infectious diseases should be expected.

Yet if we take a snapshot of the US situation in the Nineties, compared to a limited number of cases of some diseases (including polio, diphtheria, tetanus, measles)3 there are still numerous cases of varicella, or chickenpox, (for which a vaccine did not yet exist ). In the United States, before 1995, the year in which the vaccine was introduced, there were about 4 million cases of chickenpox every year, cases that the good hygienic conditions in the country could not prevent4. The introduction of the vaccine led to a collapse of varicella cases with a decrease of 45% from 2000 to 2005 and with a further drop of 77% from 2006 to 2010 (after the recommendation to give two doses of vaccine), determining an overall fall of 82% in cases from 2000 to 20105.

Si consideri poi il caso del vaccino contro Haemophilus influenzae tipo b (Hib).

The conjugate vaccine - which can be used to vaccinate children - was introduced in the United States in 1990. At that time, Hib was the most common cause of bacterial meningitis, responsible for 15,000 cases and 400-500 deaths each year. The number of cases of Hib meningitis and deaths has been stable for decades. Following the introduction of the haemophilus vaccine, the incidence of Hib meningitis fell to less than 50 cases per year6. As the current sanitation level is no different from that of 1990, it is difficult to attribute this drastic reduction in Hib pathologies to anything other than the vaccine.

An additional method to evaluate the impact of vaccinations on the incidence of diseases is to examine the impact of diseases in a community with good socio-economic conditions but low vaccination coverage rates. It is thus possible to assess the situation in developed countries where there has been a decrease in vaccination coverage in the population and to observe what happened.

- In the Netherlands, the national vaccination programme began in 1957. Despite high vaccination coverage, in recent decades there have been epidemics of poliomyelitis (1992-1993), measles (1999-2000), rubella (2004-2005) and mumps (2007-2008). These epidemics have all been largely confined to an area of the country known as the Bible Belt, where Orthodox Protestant groups live. Almost all patients in these outbreaks belonged to the Orthodox Protestant minority and were not vaccinated due to religious objections7. Another similar example is that of the Orthodox Jews who constitute a minority in Europe. Many of them refuse vaccinations and in recent years have experienced significant measles epidemics.

- MMR vaccination was introduced in Britain in 1988; over 7 years (1995) a vaccination coverage of 90% was reached with a decrease in reports of the disease. However, at the end of the 1990s, the controversy over the safety of the MMR vaccine (the Wakefield affair) led to a decrease in vaccination coverage and the recurrence of measles. In May 2006, 449 cases were confirmed (compared to 77 in 2007) with the first measles death recorded since 19929.

- In the mid-1970s there was a decrease in vaccination coverage for pertussis (whooping cough) in various countries (due to a fear linked to the possible side effects of the vaccine). In Japan in 1979 there were 13,000 cases of pertussis and 41 deaths. Similar epidemics have also occurred in the UK and Sweden10.

Consider two further examples:

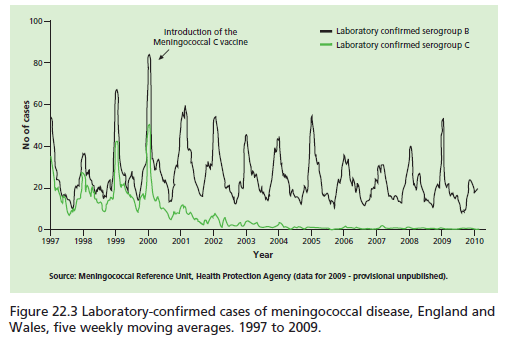

Great Britain - meningococcus vaccination

In November 1999, the meningococcal C conjugate vaccine was introduced in the UK as one of the routine vaccinations. All children and adolescents under the age of 18 were vaccinated within 2 years (a campaign that was extended in 2002 to all individuals under the age of 25).After the meningococcus C vaccination campaign, the number of laboratory-confirmed serotype C cases decreased by 90% in all age groups of those vaccinated. This, however, was not the case with meningococcus B, which the vaccine did not protect against 11.

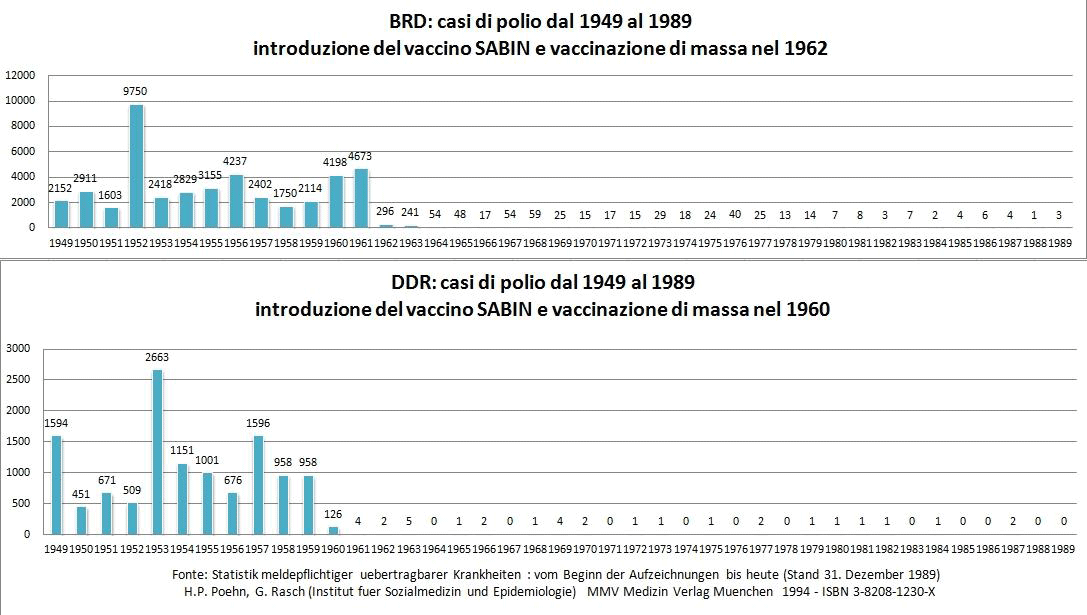

Germany - poliomyelitis vaccination

The two graphs reflect the reality of East (DDR) and West (BRD) Germany regarding polio vaccination. The two countries introduced the Sabin vaccine in two different years - 1960 and 1962 - and it can be seen that the drop in polio cases coincides with the introduction of vaccination.

Conclusions

The above data shows that not only would the diseases have failed to disappear without vaccines but, if vaccination were to stop, the diseases would reappear. Unfortunately, improved living standards and sanitation cannot guarantee protection from infectious diseases.

Sources / Bibliography

- Public Health Agency of Canada, Canadian Immunization Guide, (part 4) 2012

- Assael BM. Il favoloso innesto: storia sociale della vaccinazione, 1995

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Impact of vaccines universally recommended for children--United States, 1990-1998. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999 Apr 2;48(12):243-8

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Decline in annual incidence of varicella—Selected Stases, 1990-2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003 Sep 19;52(37):884-5

- CDC-Monitoring Varicella

- Offit PA, Bell, LM. “Vaccines: what you should know”, 2003, p. 92-115

- Ruijs WL, Hautvast JL, van der Velden K, de Vos S, Knippenberg H, Hulscher ME. Religious subgroups influencing vaccination coverage in the Dutch Bible belt: an ecological study. BMC Public Health. 2011 Feb 14;11:102

- Muscat M, Bang H, Wohlfahrt J, Glismann S, Mølbak K; EUVAC.NET Group. Measles in Europe: an epidemiological assessment. Lancet. 2009 Jan 31;373(9661):383-9

- Asaria P, MacMahon E, Measles in the United Kingdom: can we eradicate it by 2010? BMJ. 2006 October 28; 333(7574): 890–895

- Gangarosa EJ, Galazka AM, Wolfe CR, Phillips LM, Gangarosa RE, Miller E, Chen RT. Impact of anti-vaccine movements on pertussis control: the untold story. Lancet. 1998 Jan 31;351(9099):356-61

- Green Book 2011