The hypothesis

The hypothesis that cot death (or Sudden Infant Death Syndrome, SIDS) is caused by the DTP (diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis) vaccine was out forward by Dr. Viera Schneiber, a retired researcher with a PhD in micropaleontology but no formal experience in the medical field and one of the leading exponents of the anti-vaccination movement in Australia. In the last twenty years, she has travelled the world promoting her theories, claiming that vaccines are ineffective and harmful. Her interest in vaccines dates back to 1985, when, while testing a device to monitor breathing in infants (called ‘cotwatch’), which was invented and developed by her husband, she observed periods she called ‘stressed breathing’ (respiratory distress) in children who were had been vaccinated a few days previously with the DTP vaccine. She therefore suggested that vaccination with DTP was the cause of cot death1.

Scientific elements that refute a causal relationship between the DTP vaccine and cot death

Cot death is defined as the death of a seemingly healthy baby during its first year of life and does not correspond to a specific pathology: death is ascribed to SIDS when all other causes of death of the newborn can be ruled out (via autopsy, accurate analysis of the child's health and the circumstances surrounding his death). In developed countries the incidence varies from 0.09 to 0.8 cases per 1000 newborns. Incidences varies greatly among ethnic groups; for example, the risk of cot death increases two to seven times in Native Americans and the black population in the USA, in Maoris in New Zealand, in Australian Aborigines and in people of mixed descent in Cape Town in South Africa2.

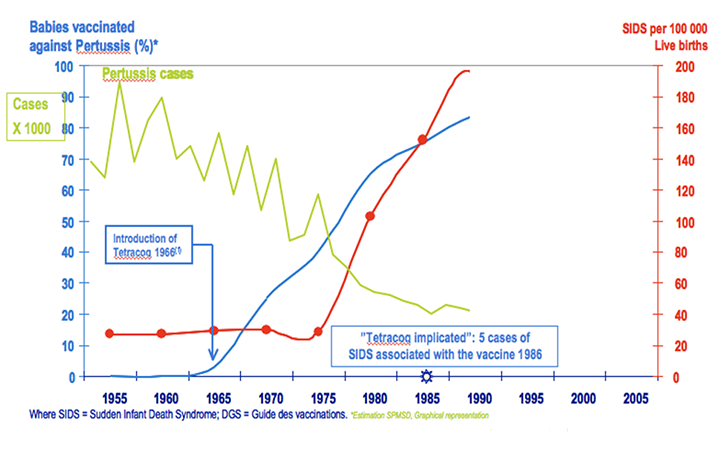

The peak incidence of cot death is between 2 and 4 months of age; this is also the age at which vaccinations for children begin. The temporal relationship of these two events can lead to the suspicion of a cause-effect relationship between the two. However, numerous studies have allowed us to rule out a causal relationship between vaccines and cot death 3-4-5-6.

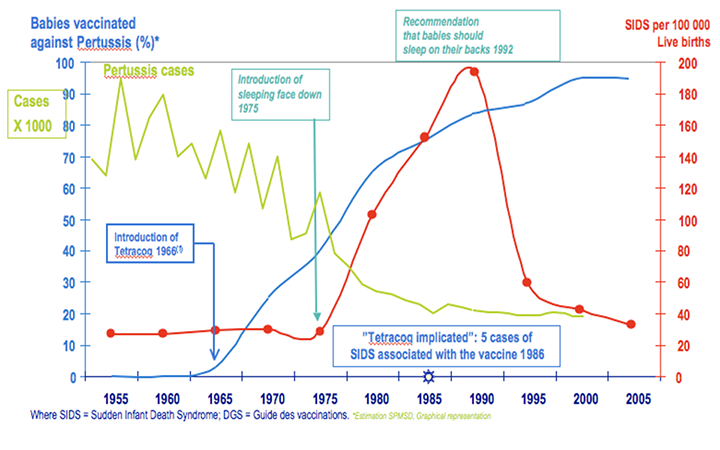

In fact in the 1970s in many European countries (France, Norway, Sweden, Denmark, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands), there was a constant increase in cases of cot death (graph 1), followed by a drop in cases around 1992. In retrospect, it seems certain that the practice of putting newborns to sleep in a prone position, introduced in Europe from the USA in the 1970s, was the cause of this increased neonatal mortality (graph 2). The abandonment of this practice led to an extraordinary and sudden drop in cot deaths in all countries.

In the USA, thanks to numerous prevention campaigns and the recommendation to put babies to sleep on their backs (supine position), between 1992 and 1998 the proportion of children put to sleep in a prone position fell from 70% to 17% and cot death rates were reduced by around 40% from 1.2 to 0.72 cases per 1000 newborns7.

It is estimated that having babies sleep on their backs has saved around 850 children a year in Australia and other countries8.

Conclusions

The hypothesis that cot death is related to vaccination - and specifically to the Diphtheria-Tetanus-Pertussis vaccine - has been refuted by numerous studies. There are several risk factors for the occurrence of cot death, both intrinsic to the newborn and extrinsic. The most important and most effective recommendation to prevent cot death is to put the child sleep on his/her back.